PRESS & NEWS

FTD Registry Research Survey Results – Summer 2020

Knowledge gained from participation in FTD Disorders Registry research surveys helps advance science toward finding treatments and a cure for FTD.

Knowledge gained from participation in FTD Disorders Registry research surveys helps advance science toward finding treatments and a cure for FTD.

Have you wondered about participating in research and being part of the discovery of treatments and a cure for frontotemporal degeneration (FTD)? Maybe you are already enrolled in a clinical trial? Perhaps you have joined the FTD Disorders Registry (FTDDR), consented for research, and completed surveys to share your story? Or maybe you want more information before deciding if research is right for you?

“Participating in research has many advantages to persons diagnosed with FTD and their families,” said FTD Registry Director Dianna Wheaton, Ph.D. “These include providing special access to medical expertise and current information on emerging treatments. It also means contributing to the growing knowledge base for understanding FTD disorders.”

One of the purposes of the FTD Registry is to facilitate research. This includes both gathering information internally as well as offering eligible members opportunities to volunteer for other studies. By participating in research and completing surveys, Registry members are citizen scientists working with other scientists to drive new research, to change the way clinical trials are run, and to help answer key questions about each FTD disorder, Dr. Wheaton said.

“As a patient-centric registry, the FTD Disorders Registry seeks to empower people with knowledge and understanding while also creating the means to participate in research,” she explained. “While the Registry is an example of observational research, registries also play a central role in promoting and recruiting for external clinical studies.”

As a Research Registry, FTDDR collects information from participants who live in the United States and Canada and also emails them targeted study notices based on their research profile. (FTDDR is also a Contact Registry for persons around the world who want to receive Registry newsletters and FTD research updates.)

FTDDR administers three intake surveys to persons enrolled in the Research Registry:

“Through these surveys people describe their experiences, giving their unique perspectives that come from having a diagnosis of FTD,” said Dr. Wheaton. “Each individual’s data is combined with others to build a picture of what life is like with FTD. This lets participants learn more about the experiences of others, how much they have in common, and what makes the FTD experience different. It also helps doctors, scientists, and drug developers know more about these diseases from the patient/caregiver/family perspective so they can create appropriate research studies to test possible treatments.”

The Registry’s surveys are examples of observational studies. In these types of research, investigators watch and document the naturally occurring changes in the health, behavior, and cognitive abilities of a group of people with the same condition over a period of time. Questions raised in observational studies often become clinical trials.

In a clinical trial, the investigators evaluate the safety and effectiveness of different medical interventions, including drugs, treatments, medical devices, etc. (Read more about the clinical trial process in this article.)

In addition to administering its own surveys, the Registry collaborates with the research community by listing all kinds of FTD studies on the FIND A STUDY page of the website, by notifying potential candidates about studies for which they may be eligible, by collecting survey data on behalf of a study, and by providing de-identified data to address proposed questions whose answers are learned through studies.

This article focuses on research readiness and the thoughts and feelings of survey participants. To better understand the survey results, a glossary was created to offer definitions of words used in this article. Terms are listed in bold the first time they appear. In addition, some of the survey results are depicted in an infographic.

RESEARCH READINESS

The goal of the Research Ready Survey is to gather information about people’s knowledge, perceptions, and preferences regarding research studies and clinical trials. This information helps doctors, scientists, and drug developers design research studies and clinical trials that are disease specific and volunteer friendly.

“The data collected from the Research Ready Survey draws a picture of the willingness and ability for people diagnosed with FTD, their family members, and caregivers to enroll in research studies and clinical trials,” explained Dr. Wheaton. “Survey respondents indicate their level of research knowledge, what type of testing they are willing to undergo, and concerns they may have about participating.”

Unless otherwise stated, the data presented below covers a combination of all reporting categories — diagnosed persons, biological relatives, and spouse/caregivers. Separate research surveys and clinical trials are offered to persons in each of these three categories. Often biological relatives, spouses, and caregivers are enrolled in studies as at-risk relatives or normal controls.

Among FTDDR research participants, the perceived value of clinical trials is high (85%). This includes that these studies help patients and society, help increase what is known about FTD diseases, help provide access to new treatments, and help test drugs and move them through the approval process. Only 2% of Registry research participants feel that clinical trials are biased, risky, too expensive, not inclusive, and/or a waste of time. The remaining respondents indicated that they were neutral.

Similarly, 84% of the participants have a positive impression of studies and are very willing to participate. Only 3% indicated that they were highly unlikely to participate. The rest were neutral.

When delving deeper into motivations about participating in research, all respondents indicated several reasons they would be willing to join a study, including in descending order: if the study was about treating the disease, if they received an explanation of the study’s results, if the study was about preventing FTD, if they or someone they know has FTD or a gene mutation that puts them at risk of getting the disease, if they received a summary of their data, and if the study was about testing drugs to manage difficult symptoms of the disease. (See infographic for details.)

Specifically, FTD-diagnosed individuals were more likely to participate if the study was about treating the disease or testing drugs to manage symptoms and because they would receive a summary of their data. Biological relatives were more likely to participate in research to prevent FTD or because they or someone they know has FTD or a gene mutation that puts them at risk of getting the disease.

Most participants (80%) of each category are willing and interested in participating in natural history studies which do not require the testing of drugs.

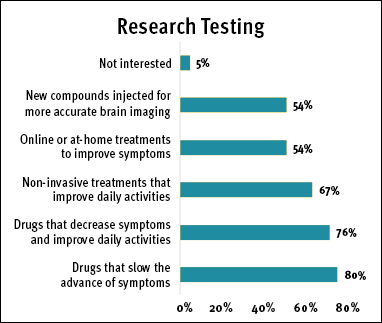

Those diagnosed with FTD indicated that they were most likely to participate in studies in which the efficiency of drugs to manage FTD symptoms was being tested. They were also comfortable with non-invasive procedures and online or at-home treatments. A small percentage of respondents were not interested in participating in a study. (See Research Testing chart.)

Those diagnosed with FTD indicated that they were most likely to participate in studies in which the efficiency of drugs to manage FTD symptoms was being tested. They were also comfortable with non-invasive procedures and online or at-home treatments. A small percentage of respondents were not interested in participating in a study. (See Research Testing chart.)

In addition, FTD-diagnosed persons were asked which procedures they were willing to undergo for a research study or clinical trial. (See infographic for details.) From most to least likely, responses included:

- Blood sample collection

- Answering detailed questions

- Genetic testing

- EEG recording (wearing sensors to track brain activity)

- PET scans

- MRI scans

- Skin biopsy (remove a small piece of skin from forearm)

- Sleep analysis

- New drug safety/tolerance testing

- Lumbar puncture, also knowns as a spinal tap (sample of fluid removed from the spine)

- Not willing to undergo extra procedures not part of routine clinical care

Caregivers, spouses, family members, and friends who completed Registry surveys were asked if they would be interested in acting as THE care partner for an FTD-diagnosed person participating in research. This requires accompanying them to each site visit or being present for phone calls or online teleconferences. Almost half said “yes” and more than a quarter said “no” with the remaining not sure.

“Participating in research necessitates commitment by both the FTD-diagnosed person and a care partner,” noted Dr. Wheaton. “The travel distance and time for visits to clinical sites can be challenging.”

“Participating in research necessitates commitment by both the FTD-diagnosed person and a care partner,” noted Dr. Wheaton. “The travel distance and time for visits to clinical sites can be challenging.”

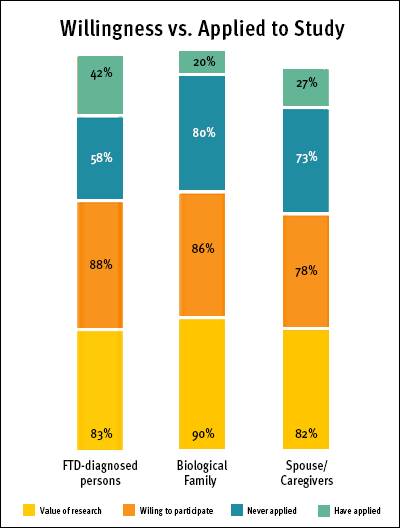

While interest, willingness, and value of clinical trials were ranked high by all, the percentage of respondents who have actually applied to participate in an FTD research study or clinical trial varied. More than double the number of FTD-diagnosed individuals than biological family members, spouses, and caregivers had applied to participate in research. Meanwhile, biological family members were most likely to have never applied to a study. (See Willingness vs. Applied to Study chart)

UNDERSTANDING RESEARCH

While most Registry Research participants appreciate the value of research and have a positive impression of it, their level of understanding concepts and design of clinical trials varies. Some feel very knowledgeable and understand concepts such as placebo, randomization, and trial phases (31%); others somewhat understand concepts (32%); and still others only understand a few basic concepts such as informed consent to participate and standard care versus research care (30%). There were 8% who think clinical trials are just extra tests and paperwork at a doctor’s visit. Of those who indicated a poor concept of clinical trial concepts and designs, three-quarters noted that additional information and education about basic research concepts and terminology might help them decide whether to participate.

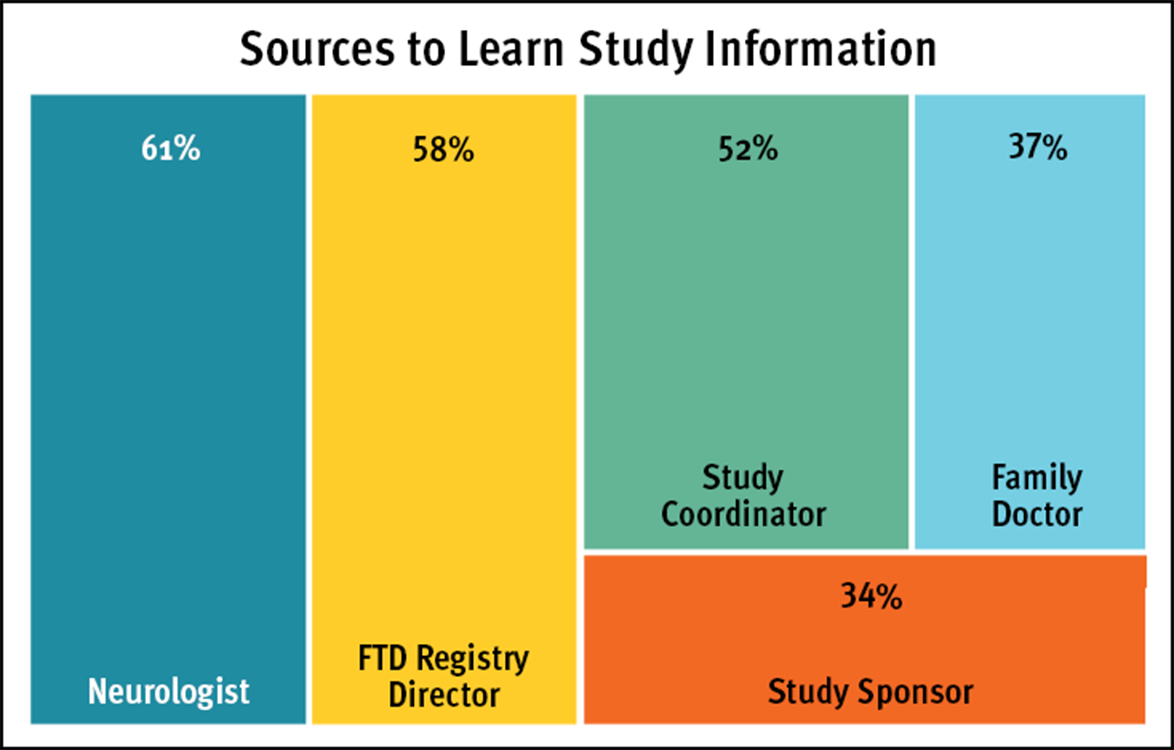

When asked about what sources might encourage a person to participate in a research study or clinical trial, most are comfortable learning from several different places, especially a neurologist and the FTD Registry Director. (See Sources to Learn Study Information chart)

When asked about what sources might encourage a person to participate in a research study or clinical trial, most are comfortable learning from several different places, especially a neurologist and the FTD Registry Director. (See Sources to Learn Study Information chart)

Sources from which people would be less likely to participate or would be uncomfortable receiving study information were the study sponsor and a family doctor.

GENETIC TESTING

A genetic cause for FTD is identified in about 20% of individuals tested. These people have a mutation, or change, in a gene that has been linked to FTD. Tests for inherited forms of FTD are performed through a blood or saliva sample. According to the Penn FTD Center, the majority of FTD-diagnosed persons with a genetic mutation have one of the following genes:

- C9orf72 (often referred to as the chromosome 9 gene): Believed to be the most common genetic form of FTD, mutations in C9orf72 are estimated to account for 6% of all sporadic FTD cases and up to 25% of all familial FTD cases.

- Microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT, often referred to as “tau”): This gene carries the instructions for making the tau protein. Tau is a protein that occurs in all neurons and is essential for normal neuronal shape, functioning, and metabolism. Mutations in MAPT are responsible for 5% to 10% of all FTD cases.

- Progranulin (GRN or PGRN): This gene carries the instructions for making the progranulin protein. Granulins derived from progranulin contribute to mechanisms that protect neurons from different types of injury, such as inflammation, and help with neuronal repair after an injury. Mutations in GRN account for 5% to 10% of all FTD cases.

- Valosin-Containing Protein (VCP): These mutations are associated with a specific condition called inclusion body myopathy with Paget disease of the bone and FTD (IBMPFD). VCP mutations account for a very small percentage of FTD cases, approximately 1% to 2%.

Three additional genes that have been associated with extremely rare FTD cases are:

- Charged multivesicular body protein 2B (CHMP2B): This is so rare that it has only been found in a few families worldwide.

- TAR DNA-binding protein (TARDBP): This is more associated with hereditary ALS than FTD.

- Fused in sarcoma (FUS): This is more associated with hereditary ALS than FTD.

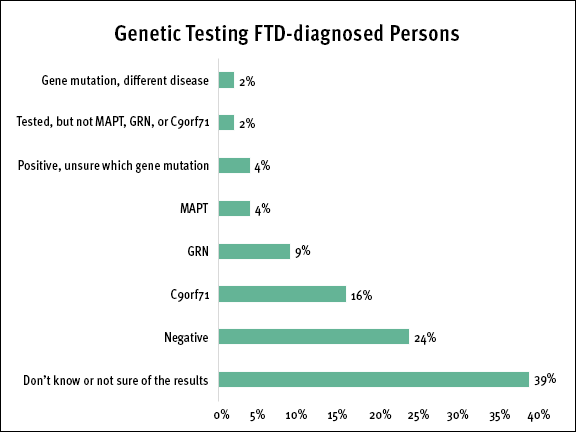

Almost a quarter of FTD-diagnosed persons noted that they have been tested for a genetic mutation. (See Genetic Testing FTD-diagnosed Persons chart) Of those who have not been tested, more than two-thirds said that if genetic testing were available that they would like to be tested. (See infographic for more details.)

Almost a quarter of FTD-diagnosed persons noted that they have been tested for a genetic mutation. (See Genetic Testing FTD-diagnosed Persons chart) Of those who have not been tested, more than two-thirds said that if genetic testing were available that they would like to be tested. (See infographic for more details.)

For biological family members, most have not had genetic testing. Of those who reported no testing, more than half indicated they would like to be tested if it were available.

“As new treatments become available, the need for genetic testing of FTD genes will grow,” noted Dr. Wheaton. “Knowing your genetic testing status is increasingly important as some potential treatments will only work in specific genetic sub-populations.”

When asked about family history for FTD or other neurological disorders, the survey results were mixed.

FTD-diagnosed persons indicated:

- 15% have a relative with FTD

- 27% have a relative diagnosed with another neurological disease

- 38% have no known FTD or neurological disease

- 20% are unsure

Biological family members indicated:

- 20% have a relative with FTD

- 34% have a relative diagnosed with another neurological disease

- 35% have no known FTD or neurological disease

- 11% are unsure

BRAIN DONATION

BRAIN DONATION

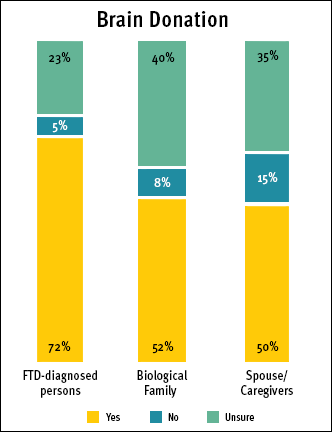

FTD-diagnosed persons feel that providing their brain and other tissues at autopsy is critical for researchers, especially if they have been regularly tracked by their doctor. Spouses and caregivers who donate their brains to research participate as normal controls. (Read more about brain donation here.)

All three categories of survey participants were asked their opinion about donating their brain to research. The majority were inclined to do so, however, several were undecided. (See Brain Donation chart)

BENEFITS, BARRIERS, & RISKS

“Taking part in Registry research may not benefit the participant personally, medically, or financially. However, it may benefit them and the FTD community by helping researchers better understand these rare and debilitating disorders,” explained Dr. Wheaton. “Analyzing the collected data may help speed up research to find and test potential treatments, and they may result in other medical advances to improve the outlook for individuals diagnosed with FTD disorders.”

The willingness of individuals to participate in research studies shows that the benefits outweigh the drawbacks. However, there are some reasons that discourage or prevent some people from applying to studies. Survey results showed that concerns people have include, from greatest to least:

- Fear that the research study or clinical trial will be too difficult physically or emotionally

- Concern about taking time off from work (for self or care partner)

- Concern that they will not be reimbursed for all or most travel expenses

- Being treated like a guinea pig

- Concern that their identity would not be kept private

- Fear of learning too much about the disease

- Not having a care partner who can accompany them to visits

Several respondents wrote in additional barriers that prevented them from participating, which included:

- Age

- Apathy

- Childcare

- Drugs: some did not want to take drugs, while others were concerned about existing allergies, side effects, and toxicity

- Fear of knowing the study's results, specifically genetic testing

- Fear of invasive testing, specifically lumbar puncture

- Fear of painful procedures

- Insurance implications

- Other existing health issues

- Other family responsibilities

- Time: lack of time, time away from home, time required for travel

- Travel too difficult

The above concerns were noted by all FTDDR Research Registry members, however, biological relatives had higher concerns about themselves or care partners needing to take time off from work for research studies than indicated by those diagnosed with FTD, their spouses, caregivers, and friends. Biological family members also indicated a greater fear of learning too much about the disease and of their identity not being kept private.

Most survey respondents indicated that they would be willing to complete surveys that asked about their experiences of participating in studies. Interestingly, the majority of this data about research readiness was submitted by people who completed the survey before the coronavirus pandemic began, which paused many studies that required in-person site visits.

Most FTD-diagnosed persons indicated that if their daily symptoms made participating in a study difficult because of travel or the amount of time at the doctor's clinic that they would still like to participate in research if other options were made available, including:

- Sharing experiences from home using online software (Skype, Zoom, etc.)

- Wearing a tracking device such as a smartwatch (Fitbit, Apple Watch, etc.)

- Having a health professional come to the home for certain aspects of the study

All research studies have eligibility criteria for which a participant must meet. These consist of reasons to qualify (inclusion criteria) and reasons to not qualify (exclusion criteria). Sometimes inclusion criteria is broad in scope, such as being a person diagnosed with any type of FTD or perhaps the caregiver to someone with dementia. Other times it may be specific, such as being diagnosed with a certain type of FTD or having a particular genetic mutation. Oftentimes concurrently participating in an interventional trial or taking a specific type of medication will exclude someone from another study. Registry research has fewer barriers to participation than most clinical trials.

There are risks when participating in Registry research, but in general, they are low, Dr. Wheaton said. “By looking at the data contributed by all participants, a person may learn information that is difficult or upsetting to them. They may find that some of the questions asked in the surveys are embarrassing, hard, or uncomfortable to answer. However, the answers are important to learn about FTD.”

When people register to be an FTDDR research participant, they are assigned a unique code with numbers and letters called a Global Unique Identifier, or GUID. The GUID is associated with the data that is entered so the person’s identity remains anonymous. This ensures your identity cannot be linked to a research survey or other study.

“The Registry will not keep or report data in a way that someone can be identified by their answer,” Dr. Wheaton noted.

Participants’ information is stored in a secure online database. Risks are minimized through procedures that comply with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) rules and standards, Canadian privacy laws, and the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Participating in medical research has advantages for persons diagnosed and their families. These include providing special access to medical expertise and current information on emerging treatments. It also means contributing to the growing knowledge base for understanding FTD disorders. Finally, being part of research means helping advance the science to benefit others affected by FTD in the future.

Are you ready and willing to participate in research?

Together we can find a cure for ftd

The FTD Disorders Registry is a powerful tool in the movement to create therapies and find a cure. Together we can help change the course of the disease and put an end to FTD.

Your privacy is important! We promise to protect it. We will not share your contact information.